Introduction: The ‘Renovation’ Meets Legislative Reality

The clinical research community has long navigated the “GCP Renovation,” a strategic modernization effort initiated in 2017 to address the escalating complexity of clinical trial designs and the digital ecosystem. With the formal adoption of ICH E6(R3) on 06 January 2025, the industry moved from high-level reflection papers to a concrete, albeit highly flexible, international standard. However, for those operating within the United Kingdom, this is not a simple “copy-paste” exercise of a global text. Instead, it represents a sophisticated intersection where international harmonization meets the specificities of the UK’s legislative framework, overseen by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the Health Research Authority (HRA).As a clinical regulatory consultant, I often see sponsors struggle with the “translation gap”—the space between global principles and local statutory enforcement. The R3 update is designed to be “media neutral” and “proportional,” but in the UK, these concepts must be reconciled with the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004, which were notably amended in 2025. Navigating this landscape requires moving beyond rigid, one-size-fits-all checklists toward a culture of “Quality by Design” (QbD). This shift demands that we stop treating GCP as a burden to be managed and start treating it as a strategic framework for trial efficiency.

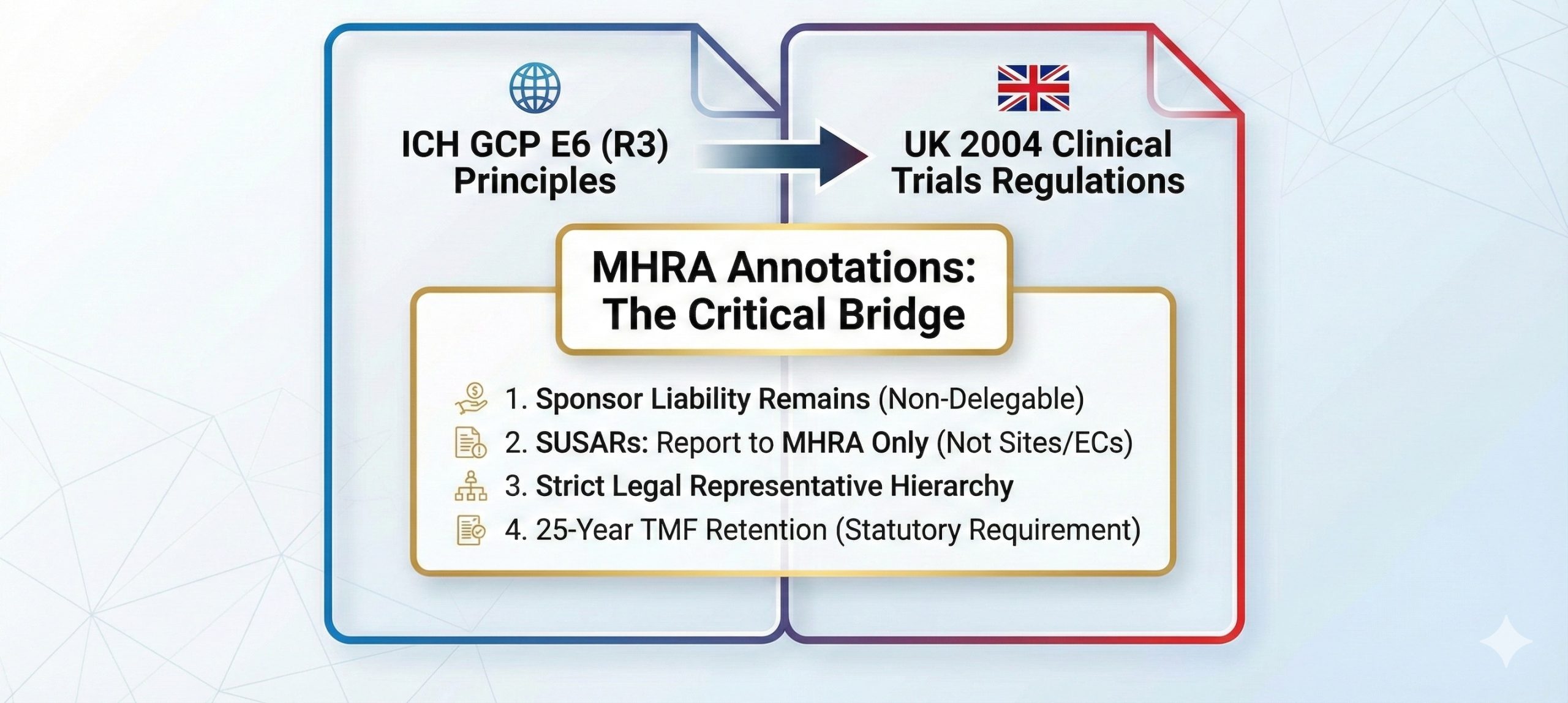

The Status of ICH E6(R3) in the UK

While ICH E6(R3) provides the harmonized global framework for trials intended for regulatory submission, its legal standing in the UK is governed by statute. In the UK, all clinical trials of Investigational Medicinal Products (IMPs) must be conducted according to Good Clinical Practice as set out in the 2004 Regulations (as amended). Crucially, the UK annotations clarify that these principles apply to all IMP trials, regardless of whether the data is intended for a Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA).From a strategic standpoint, sponsors must understand the nuances of delegation. While the UK utilizes a streamlined application process, the legal accountability remains fixed.Per Regulation 16(1), the UK mandates a single application dossier—the “request for approval”—covering both the MHRA licensing authority and the HRA ethics committee opinion. Under Regulation 3(12), while a sponsor may delegate the function of making this application (e.g., to a CRO), such an arrangement does not affect the ultimate responsibility of the sponsor. Strategic oversight is not just a GCP principle; it is a statutory requirement that cannot be contracted away.

Takeaway 1: The End of “Error-Free” Data Perfectionism

One of the most impactful shifts in the R3 update is found in Principle 6 and Principle 7, which redefine quality as “Fitness for Purpose.” The guideline moves away from the traditional, and often prohibitively expensive, pursuit of “perfect” data. It introduces a reality where data does not need to be error-free if it supports conclusions and interpretations equivalent to those derived from error-free data.This is a profound change for Clinical Quality Management. For years, monitoring budgets have been consumed by intensive Source Data Verification (SDV) of non-critical fields. By focusing on “Critical to Quality” (CtQ) factors, sponsors can reallocate resources from administrative data-cleaning to proactive risk management. This proactive stance is the heart of Quality by Design.”Quality by design should be implemented to identify the factors (i.e., data and processes) that are critical to ensuring trial quality and the risks that threaten the integrity of those factors and ultimately the reliability of the trial results.” (ICH E6(R3) Section II)By identifying these factors prospectively, trialists can implement mitigation strategies that focus on what truly impacts participant safety and result reliability. If a data point does not influence the primary endpoint or a safety signal, R3 suggests we should treat it with proportionate oversight, not obsessive perfectionism.

Takeaway 2: The UK’s Counter-Intuitive Stance on Periodic IRB Review

A significant point of divergence for international sponsors is the UK’s interpretation of Principle 3.2. While the ICH text suggests that “periodic review of the trial by the IRB/IEC should also be conducted,” the UK-specific annotations provide a critical clarification.In the UK, there is no legal requirement for an Ethics Committee to undertake periodic reviews of a clinical trial once it has been approved. For sponsors used to the administrative cycle of annual renewals in other regions, this is a major “surprising” reality. However, this does not imply a lack of oversight. The HRA remains engaged through:

- Substantial modifications to the trial (Regulations 22-22C).

- Urgent safety measures (Regulation 30).

- Serious breaches (Regulation 29A).

- Annual safety reports (Regulation 35).This approach reduces administrative “busy work” while ensuring that the Ethics Committee focuses on high-impact changes and safety data rather than routine calendar-based renewals.

Takeaway 3: The “Delegation Log Diet” – Trimming Routine Care

ICH E6(R3) Annex 1 (Sections 2.3.3 and 3.6) introduces much-needed flexibility regarding the documentation of trial activities. The UK interpretation of these sections provides a strategic opportunity to “diet” the delegation log.The MHRA has clarified that individuals performing trial activities as part of routine clinical care do not necessarily need to be listed on the delegation log. Furthermore, Section 2.3.2 specifies that trial-specific training—including formal GCP training—should only be required for activities that go beyond an individual’s usual training and experience .From a consultant’s perspective, this is a call to action. We have seen “bloated” delegation logs where every nurse on a ward is listed because they might take a blood sample. If that nurse is taking a sample exactly as they would for any other patient, R3 and the UK annotations suggest they should be excluded from the log.Maintaining a 50-person delegation log for a simple trial creates an unnecessary maintenance burden and, ironically, obscures oversight. When an investigator signs off on a massive list of routine staff, they dilute their ability to demonstrate meaningful oversight of the staff performing critical trial-specific procedures. The “Diet” is about clarity, not just reduction.

Takeaway 4: A Decisive Break from SUSAR “Inbox Spam”

Safety reporting undergoes a strategic overhaul in R3 (Section 3.13.2). Historically, investigators were inundated with individual Suspected Unexpected Serious Adverse Reactions (SUSARs) from around the globe, often leading to “inbox spam” that obscured genuine local safety signals.The UK environment has moved decisively to streamline this:

- Direct Reporting: There is no legal requirement to report individual SUSARs to investigators or Ethics Committees; they are reported directly to the MHRA.

- Urgency Over Arbitrary Timelines: The strict 7/15-day timeline for notifying investigators and IRBs has been replaced. Section 3.13.2(d) now requires reporting to reflect the “urgency of action required.”

- Alternative Arrangements: Section 3.13.2(f) introduces the possibility of “alternative arrangements” for safety reporting, such as selective safety reporting in late-stage trials (referencing ICH E19).This allows sponsors to move away from individual reports and toward aggregated safety information, providing investigators with a meaningful assessment of the evolving benefit-risk profile rather than isolated data points.

Takeaway 5: Data Governance – More Than Just “Computer Validation”

The introduction of Section 4, “Data Governance,” is the most modernizing element of ICH E6(R3). It shifts the focus from simple technical “validation” to the entire “Data Life Cycle.” For the UK, this must be synthesized with the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018 .Under Section 4.3, sponsors and investigators must ensure that computerized systems are “fit for purpose” through risk-based validation. Key elements include:

- Security (4.3.3): Protecting data from unauthorized access or alteration.

- Validation (4.3.4): Systems must handle data reliably, with the level of validation proportionate to the risk.

- User Management (4.3.8): Secure, attributable access and timely revocation of permissions (a point emphasized in Annex 1, 2.12.10b).

- Data Life Cycle (4.2): Including Capture, Metadata/Audit Trails, Transfer/Migration, and Retention.This is no longer an “IT function.” It is a core clinical activity. The UK expectation is that data governance ensures both the privacy of participants (per HRA guidance) and the reliability of the final results.

MHRA Inspection Focus & Demonstrating Compliance

UK inspectors look for “good evidence”—not just volume, but the alignment between process, documentation, and behavior. A strategic TMF is not one that has “everything,” but one that has the right things, documented with the correct rationale .

| Regulatory Anchor | UK/MHRA Interpretation | Practical Stakeholder Expectation || —— | —— | —— |

| Principle 1.5: Medical Responsibility | Medical care responsibility must rest with a qualified physician/dentist. | The Chief Investigator (CI) must be a physician/dentist to hold overall medical responsibility. |

| Principle 2.1: Consent Identity | Investigators must assure themselves of the participant’s identity. | Use of the MHRA/HRA joint statement on electronic methods for remote identity verification. |

| Principle 11.5: IMP Labeling | Labeling must comply with local statutory requirements. | Labels must follow Part 6 of the UK Clinical Trials Regulations and robustly protect the blinding. || Principle 9.5: Record Retention | Records must be retained for the “required period.” | TMF retention must comply with Regulation 31A of the UK Clinical Trials Regulations (or Schedule 14 for older trials). |

| Principle 10.1: Delegation | Overall responsibility remains with the sponsor despite delegation. | Evidence of “oversight” (e.g., review of CRO performance metrics) rather than just a signed agreement. |

Common Misinterpretations: Myth vs. Fact

- Myth: “Principles-based” GCP means we can provide less documentation.

- Fact: Proportionality means rationalized documentation. You must document the rationale for risk-based decisions. If you choose not to monitor a specific site on-site, you need a documented risk assessment as per Section 3.11.4.

- Myth: Delegating a task to a service provider (CRO) reduces the sponsor’s accountability.

- Fact: Per Regulation 3(12) and ICH Principle 10.2, the sponsor retains ultimate responsibility. Oversight is a non-delegable duty.

- Myth: Modern cloud-based systems from reputable vendors do not require validation.

- Fact: Section 4.3.4 requires that computerized systems be validated for their intended use in the trial. Even if the vendor is reputable, the sponsor must ensure the specific implementation is fit for purpose.

- Myth: ICH E6(R3) replaces existing UK law.

- Fact: ICH is a guideline for harmonization. In the UK, the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 (as amended in 2025) remains the statutory authority. Where a guideline suggests a practice that contradicts law, the law prevails.

Conclusion: The Future of UK Clinical Trials

The “renovation” of GCP represents a pivot toward an intelligent, evidence-based approach to trial conduct. By embracing proportionality, UK clinical trialists can dismantle administrative burdens that add no value to participant safety or data integrity. However, this flexibility requires a higher degree of professional judgment. We are moving from a world of “following the rules” to a world of “managing the risks.”Key Takeaways for UK Trialists:

- Identify CtQ Factors: Define what is critical to your trial’s success before the first patient is screened.

- Consult the Annotations: Use the UK-specific annotations to reconcile ICH principles with UK statutory law.

- Strategic Logs: Apply the “Diet”—exclude routine clinical staff and those whose trial tasks do not exceed their professional experience.

- Safety Efficiency: Implement alternative safety reporting arrangements where appropriate, focusing on signal detection rather than “SUSAR spam.”

- Data Lifecycle Governance: Address Section 4 requirements (Security, Validation, User Management) as part of the trial design, not as a post-hoc IT check.

- Prioritize Transparency: Ensure results are published in public registries within 12 months of trial conclusion, as per Regulation 25.As we transition into this new era, the fundamental question for every Sponsor and Investigator is no longer “Did we follow the checklist?” but rather:

“How has our application of proportionality made this trial safer for the participant and the results more reliable for the regulator?”